This concludes our series on portfolio management and Seth Klarman, with ideas extracted from old Baupost Group letters. Our Readers know that we generally provide excerpts along with commentary for each topic. However, at the request of Baupost, we will not be providing any excerpts, only our interpretive summaries. For those of you wishing to read the actual letters, they are available on the internet. We are not posting them here because we don’t want to tango with the Baupost legal machine.

Volatility, Psychology

Even giants are not immune to volatility. Klarman relays the story of how Julian Robertson’s Tiger Fund closed its doors largely as a result of losses attributed to its tech positions. As consolation, Klarman offers some advice on dealing with market volatility: investors should act on the assumption that any stock or bond can trade, for a time, at any price, and never enable Mr. Market’s mood swings to lead to forced selling. Since it is impossible to predict the timing, direction and degree of price swings, investors would do well to always brace themselves for mark to market losses.

Does mentally preparing for bad outcomes help investors “do the right thing” when bad outcomes occur?

When To Buy, When To Sell, Selectivity

Klarman outlines a few criteria that must be met in order for undervalued stocks to be of interest to him:

- Undervaluation is substantial

- There’s a catalyst to assist in the realization of that value

- Business value is stable and growing, not eroding

- Management is able and properly incentivized

Have you reviewed your selectivity standards lately? How do they compare with three years ago? For more on this topic, see our previous article on selectivity.

Psychology, When To Buy, When To Sell

Because investing is a highly competitive activity, Klarman writes that it is not enough to simply buy securities that one considers undervalued – one must seek the reason for why something is undervalued, and why the seller is willing to part with a security/asset at a “bargain” price.

Here’s the rub: since we are human and prone to psychological biases (such as confirmation bias), we can conjure up any number of explanations for why we believe something is undervalued and convince ourselves that we have located the reason for undervaluation. It takes a great degree of cognitive discipline & self awareness to recognize and concede when you are (or could be) the patsy, and to walk away from those situations.

Risk, Expected Return, Cash

Klarman’s risk management process was not after-the-fact, it was woven into the security selection and portfolio construction process.

He sought to reduce risk on a situation by situation basis via

- in-depth fundamental analysis

- strict assessment of risk versus return

- demand for margin of safety in each holding

- event-driven focus

- ongoing monitoring of positions to enable him to react to changing market conditions or fundamental developments

- appropriate diversification by asset class, geography and security type, market hedges & out of the money put options

- willingness to hold cash when there are no compelling opportunities.

Klarman also provides a nice explanation of why undervaluation is so crucial to successful investing, as it relates to risk & expected return: “…undervaluation creates a compelling imbalance between risk and return.”

Benchmark

The investment objective of this particular Baupost Fund was capital appreciation with income was a secondary goal. It sought to achieve its objective by profiting from market inefficiencies and focusing on generating good risk-adjusted investment results over time – not by keeping up with any particular market index or benchmark. Klarman writes, “The point of investing…is not to have a great story to tell; the point of investing is to make money with limited risk.”

Investors should consider their goal or objective for a variety of reasons. Warren Buffett in the early Partnership days dedicated a good portion of one letter to the “yardstick” discussion. Howard Marks has referenced the importance of having a goal because it provides “an idea of what’s enough.”

Cash, Turnover

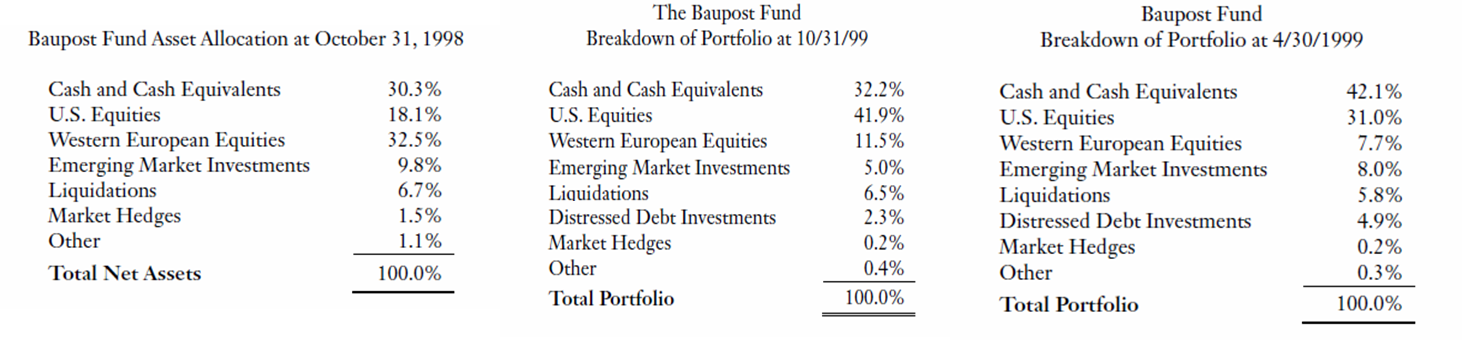

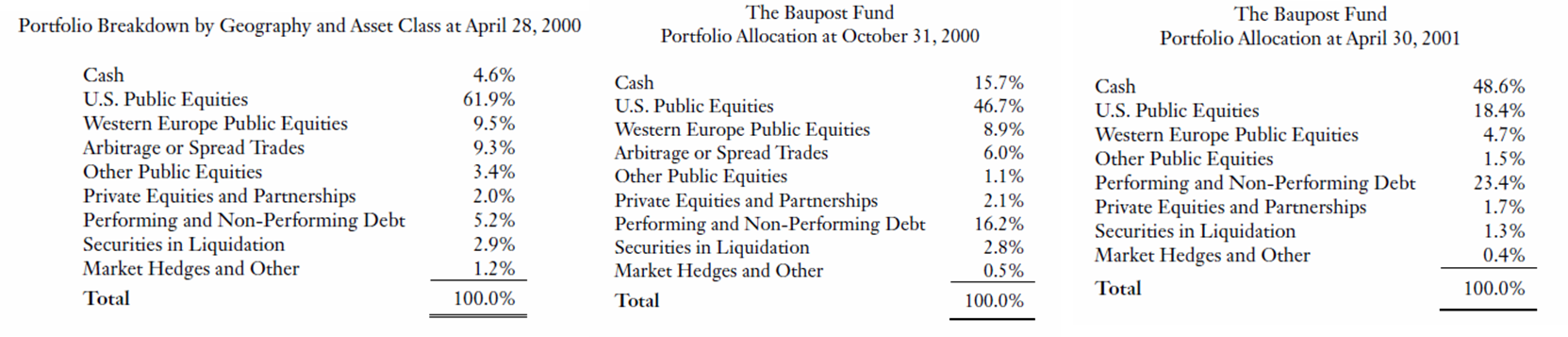

Klarman presents his portfolio breakdown via “buckets” not individual securities. See our article on Klarman's 1999 letter for more on the importance of this nuance.

The portfolio allocations changed drastically between April 1999 and April 2001. High turnover is not something that we generally associate with value-oriented or fundamental investors. In fact, turnover has quite a negative connotation. But is turnover truly such a bad thing?

Munger once said that “a majority of life’s errors are caused by forgetting what one is really trying to do.”

Yes, turnover can lead to higher transaction fees and realized tax consequences. On taxes, we defer to Buffett’s wonderfully crafted treatise on his investment tax philosophy from 1964, while the onset of electronic trading has significantly decreased transaction fees (specifically for equities) in recent days.

Which leads us back to our original question: is portfolio turnover truly such a bad thing? We don’t believe so. Turnover is merely the consequence of portfolio movements triggered by any number of reasons, good (such as correcting an investment mistake, or noticing a better opportunity elsewhere) and bad (purposeful churn of the portfolio without reason). We should judge the reason for turnover, not the act of turnover itself.

Hedging, Expected Return

The Fund’s returns in one period were reduced by hedging costs of approximately 2.4%. A portfolio’s expected return is equal to the % sizing weighted average expected return of the sum of its parts (holdings or allocations). Something to keep in mind as you incur the often negative carry cost of hedging, especially in today’s low rate environment.